Tooling up: Building a new economic mission for higher education

We argue for a fundamental shift in how the UK government conceptualises, regulates, and incentivises higher education to align it more closely with a new, proactive industrial strategy aimed at driving national economic growth and addressing regional inequalities

Date:

Authors:

01

Executive summary

The government wants economic growth. That is obvious to anyone who follows politics in even a cursory way. If the country cannot become more productive, if the economy does not grow, and if people do not feel their lives are getting better, Keir Starmer will be a one-term Prime Minister.

The government has, as an asset, a higher education system which, on many metrics, is the envy of the world. But it is also structurally disconnected from wider post-compulsory education provision, and driven almost entirely by student choice rather than the government’s economic priorities – and the current funding and regulatory arrangements do not offer many levers to government to change this. While the Secretary of State for Education has set out her priorities for higher education, there is on a daily basis in government a weak link at best between the work of the higher education system, and the work to drive economic growth.

This government has indicated its plans to make a decisive break from the broad consensus around macroeconomic strategy that has held sway in recent decades. For this administration, economic thinking requires not just a response to market failures, but a more proactive industrial strategy that takes account of a wide range of factors – geography, industry, supply chains, national security, technology – to realise the potential for growth in all parts of the country.

Previous governments’ failure to integrate skills policy, fiscal intervention, and economic reform into a framework that could deliver deeply felt and widely shared economic growth, are believed to be at the root of the malaise the country has felt since at least 2008. The last 15 years of uneven growth, low skills equilibria, regional inequality and political disengagement make the case for the new reform stronger.

Higher education policy has been guided by the older economic thinking of market-based, laissez-faire engagement, with a focus on expanding participation, student choice, competition between providers, and more recently lower barriers to entry for students and providers. For higher education to play a role in the new paradigm, government and institutions will both need to reconceptualise higher education as part of a wider system of post-compulsory education provision. Government will need to find, and higher education institutions accept, regulatory levers and incentives to align higher education provision to economic priorities as set out in the government’s industrial strategy. And all of this under considerable fiscal pressure.

This paper attempts to map the philosophical underpinnings of the shift that will be required, explain why it is necessary, and indicate some compass points for higher education reform in the forthcoming post-16 education and skills and HE reform white paper.

A quick note about scope and terms:

This paper specifically addresses higher education provision in England – which is delivered by universities, colleges, specialist providers and other higher education institutions and encompasses a range of different kinds of qualifications, including higher technical qualifications, higher and degree apprenticeships, traditional degrees and postgraduate qualifications.

02

Introduction

Growing the economy is the only hope the Labour government has of achieving any sustained electoral success. If the country cannot become more productive, if the economy does not grow, and if people do not feel their lives are getting better, Keir Starmer will be a one-term Prime Minister.

Sustained and significant economic growth is an enormous challenge. The country has been stuck in a productivity funk with people’s wages lower, their towns and cities less prosperous, and their lives less expansive, because of successive governments’ failure to recapture lost growth following the 2008 financial crash. No amount of strategies, policies, frameworks, moonshots, levelling up, fiscal bazookas, or any other number of interventions has broken the fundamental problem that the UK does not have the right people, with the right skills, in the right jobs, in the right conditions, to cumulatively make the country more productive.

While much of the public sector and further education has felt the pinch of austerity since the 2008 crash, higher education provision, particularly in universities, has been relatively well protected – grounded in a longstanding assumption among policymakers that broad investment in higher-level skills and research and innovation would pay dividends in national economic growth and productivity. Those happy times seem to be at an end. In ministerial directions, funding choices, and political rhetoric the government’s faith in the capacity of higher education and the knowledge economy to provide the economic silver bullet seems to be ebbing, with a rhetorical turn to skills and “vocational” options, particularly at sub-degree level and a parallel downplaying of the value of a traditional degree.

It is arguable whether the last 15 years of uneven growth, low skills equilibria, regional inequality and political disengagement represent a failure for the higher education sector or whether the efforts of higher education institutions have mitigated the wider problem. It is easy to point to both significant successes and failures in what is a large and diverse sector. The wider contention of this paper is that no government has yet found a way to truly harness the potential of the higher education sector in the service of economic growth, joining the policy dots in a sufficiently systematic way so as to create the right regulatory and funding incentives to orient higher education providers towards government economic priorities.

You may argue that higher education provision is not solely about economic growth and autonomous institutions are under no obligation to dance to the government’s tune. Both contentions are technically correct, but are arguably wilfully blind to the challenges the country is facing, the dependence of the sector on public money and the changing expectations of the public and policymakers of how institutions are held accountable for their use of that money when it is increasingly scarce.

The choice facing the sector, to paraphrase Universities UK president Sally Mapstone in a speech to vice chancellors at the 2024 Universities UK annual conference, is to go on like this into a period of decline, or to meet a government committed to economic growth with a vision of a reorganised sector and in doing so ensure their own sustainability, and a stronger economy.

03

A new approach to economic growth

Ever since the 1980s, successive UK administrations have embraced a single theory of economic growth. The approach, or elements within it, can be described (positively or otherwise) as “a Treasury approach”, “sound money”, “neoliberal”, “supply side”, “laissez-faire”, or “light touch”, among others.

The key aspects include:

- A belief in lightly regulated private markets as the dominant motor for economic growth;

- Using taxation and regulation, to a greater or lesser extent, as a way of redistributing the proceeds of that growth towards areas of political or economic focus;

- A belief in using state intervention, again to a lesser or greater extent, as primarily a means of addressing market failure;

- A belief in choice and contestability within both private and public markets as a way of driving innovation and lowering prices;

- A premium on maintaining control of overall money supply by the Exchequer, and holding inflation low;

- The creation of growth principally through supply side reforms including deregulation, privatisation of former state owned enterprises, deprioritisation of trade union power, and tax cuts;

- A belief in the innovative power and wealth enhancing aspects of globalisation, and support for the mechanisms that underpin this, including free trade, and lightly regulated movement of labour and capital;

- The shift of labour in higher wage economies such as the UKs into the service economy, with manufacturing being shifted to lower wage economies; and

- A strong focus on education and skills at all levels to provide a labour force that can compete and innovate globally.

There are differences between administrations, both between Conservative Prime Ministers, and especially between Conservative and Labour governments. Neither party would willingly accept a thesis of complete consistency, and indeed, measures like different volumes of public spending as a proportion of GDP do show the impact of conscious political choices. Nevertheless, these central economic tenets have remained consistent even where their application has differed between governments.

The financial crash and its legacy

The 2008 financial crisis marked the first major break in this model – certainly among the most influential politicians and policymakers holding sway in successive Whitehalls and Westminsters.

Since the crash, successive UK governments have confronted a series of pervasive and linked economic problems: low or no economic growth, low productivity, regional inequality coupled with low growth in areas outside of London, and a sizeable cohort of “left-behind” individuals and communities. A succession of further economic shocks such as Brexit, Covid-19 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have driven up the cost of living, and added to the general economic malaise. Skills England analysis of ONS labour output data suggests that had UK productivity continued to grow at the rate seen pre financial crisis, it would be nearly a third higher than it is today.

This very particular set of economic problems in the last 17 years has prompted a search for new ways of thinking about economic growth. Without economic growth and the investment in public services it enables, governments have been faced with the unenviable choice of increasing taxation or reducing spending – or both.

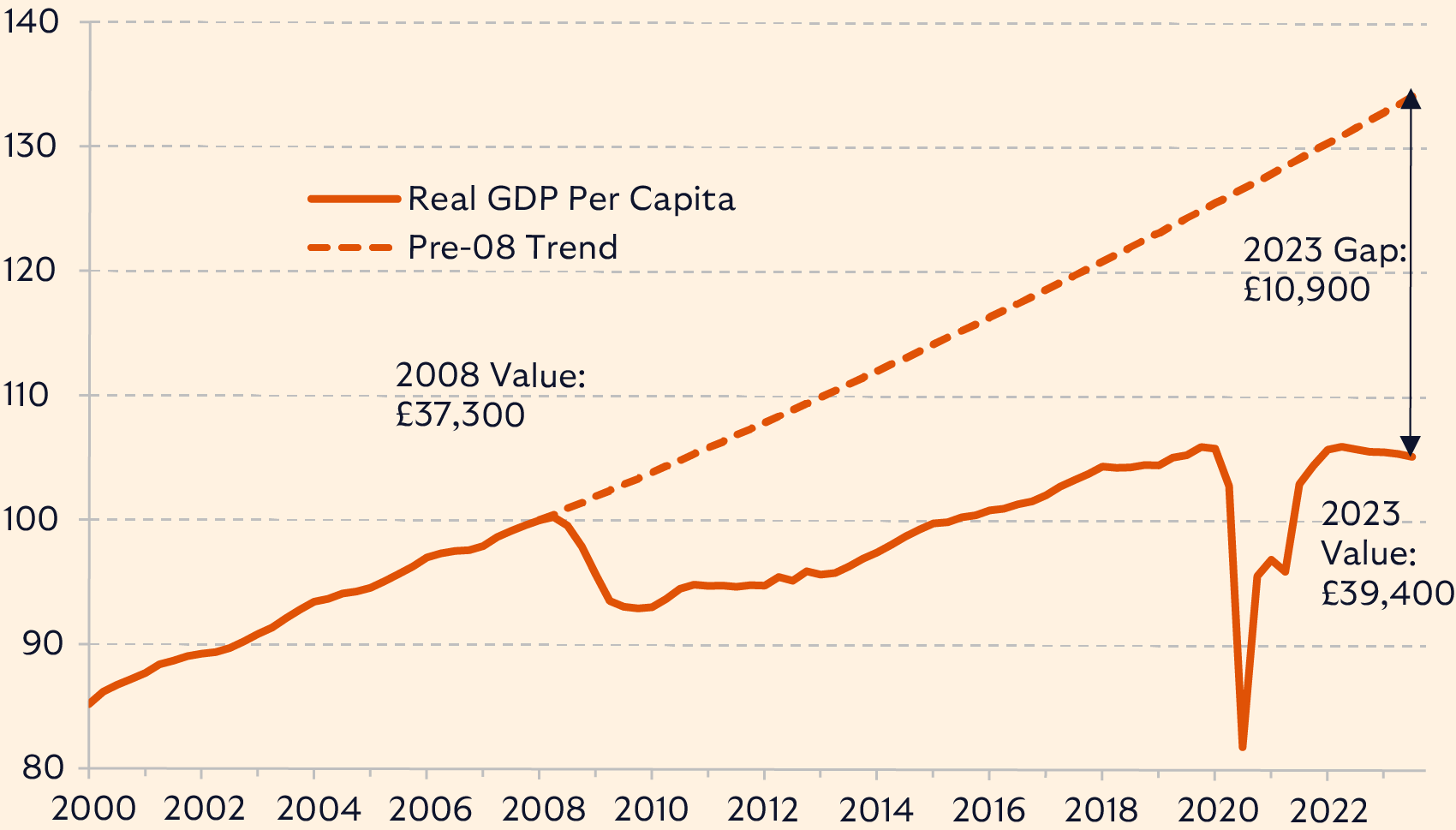

GDP per capita compared to pre-recession trend

Source: IFS, The Conservatives and the economy, June 2024.

Rachel Reeves, and making a reality of a new approach

In the months leading up to the general election of 2024, then-Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves set out her version of a new approach. In highly technocratic language, she mirrored the US take on “modern supply-side economics,” as then US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen described the Biden administration’s economic approach – known as “Bidenomics” in popular parlance in the US and “securonomics” in less popular parlance in the UK.

In a 2023 pamphlet for Labour Together, and her Mais lecture of March 2024, Reeves argued that the role of governments is to shape markets, not just “correct” them: “Governments always shape markets. Good governments consider how they do so.”

For Reeves, the new economic thinking requires not just a response to market failures, but a more proactive industrial strategy that takes account of a wide range of factors – geography, industry, supply chains, national security, technology – to realise the potential for growth in all parts of the country. Reeves’ broad themes were economic stability, removing barriers to investment and large-scale reforms to planning and regulation, as well as a focus on skills, framed as amplifying individuals’ potential to contribute to the economy.

Reeves also criticised the failure of all governments to integrate skills policy, fiscal intervention, and economic reform, into a framework that could deliver deeply felt and widely shared economic growth:

For a decade, the last Labour government offered stable politics alongside a stable economic environment. In New Labour’s analysis, growth required on the one hand macroeconomic stability, and on the other supply side policies to enhance human capital and spur innovation. What followed was a decade of sustained economic growth, stability, and rising household incomes. Average household disposable income rose by 40 per cent. Two million children and three million pensioners were lifted from poverty. Public services were revitalised.

But the analysis on which it was built was too narrow. Stability was a necessary, but not a sufficient condition to generate private sector investment. An underregulated financial sector could generate immense wealth but posed profound structural risks too. And globalisation and new technologies could widen as well as diminish inequality, disempower people as much as liberate them, displace as well as create good work.

Economic security was extended through a new minimum wage and tax credits, but our labour market remained characterised by too much insecurity. Despite sustained efforts to address our key weaknesses on productivity and regional inequality, they persisted, and so too did the festering gap between large parts of the country and Westminster politics. Most of all, the ‘great moderation’ could not last. And as the global financial crisis unfolded, these weaknesses were exposed.

Although “securonomics” was a distinctively Labour proposition, it tracked with broader trends in economic thinking. A public policy analysis from government that sought to understand the effects of geographical disparities in growth and productivity on individuals and communities, and take a strategic view of the various factors that could begin to correct these imbalances, was the basis of both Boris Johnson’s levelling up agenda and some of the domestic policy championed by Theresa May and her key advisors.

The difference between Reeves and Johnson and to a lesser extent Reeves and May is that the Chancellor has a single organising theory of growth which is anchored in sectors, places, and market reform. Reeves has alighted on an economic programme of state reorganisation, market reorientation, and addressing regional imbalances, but she is undoubtedly like her predecessors pro-market, pro-growth, and pro-business.

Industrial strategy

The industrial strategy is the Labour government’s key economic document. The draft strategy, Invest 2035, published in October 2024, seeks to realise in practice the economic principles of an activist state, identifying eight key sectors and promising to connect these more closely with places to identify “clusters” in city regions where there is untapped and/or high growth potential.

The criticism of industrial strategies is that they inevitably lead the government to attempt to pick winners and in economies of such enormous complexity they are doomed to fail and in failing they will do more harm than good. The hope of this industrial strategy is that it will create the conditions for economic success, including in regions where it promises to devolve more powers to mayoral combined authorities.

Universities may feel rather slighted about how little they are mentioned in the industrial strategy green paper – former universities minister David Willetts called this “very odd” in a paper for the Resolution Foundation. But the working strategy rightly recognises national skills and innovation capability as foundational – the challenge is to marry up university and, more widely, the breadth of higher education provision, to the priorities established through the industrial strategy. If anything, the draft strategy offers a salutary reminder that for this government higher education and research forms part of the overall economic growth and productivity puzzle; it is not viewed as a target for development in and of itself.

04

Higher education in a market-based economy

The story of university regulation and oversight in recent decades more or less reflects the approach to the macroeconomy. Under a broad knowledge economy banner governments have sought to increase the supply of human and knowledge capital through increasing participation in higher education.

Tuition fees were introduced in England in 1998 under a belief that a more massified system had to be paid for, and that ought to fall at least in part on the graduates who benefit from the economic value of a degree. As the Chancellor Gordon Brown said ahead of further tuition fees rises through the Higher Education Act 2004, “It is right that, once students become graduates, they make a greater contribution” – a key tenet of supply side or neoliberal thinking (which was not copied in other home nations). Successive rounds of tuition fee rises increased the resource to institutions and shifted the balance away from the state and taxpayer. Under the stewardship of David Willetts and subsequently Jo Johnson as universities ministers, capacity in the system also expanded with the facilitated entry to the sector of so-called “alternative providers”. Increasingly, students were positioned as “paying customers” whose choices should drive competition between higher education institutions and in doing so drive up quality.

Until 2014 the mechanism for increasing participation in higher education was still linked to the state control of the overall supply of funded places. Once the government had implemented its policy of tying to the unit of resource for teaching to the student in the form of a tuition fee loan it became possible to remove the cap on places entirely, as happened in 2015, allowing higher education institutions to recruit as many students as they wanted. In 2015 the Conservative government also introduced the Apprenticeships Levy on business to expand apprenticeship provision at every level, with provision for providers to charge higher and degree apprenticeship fees at the same level as for bachelors degrees. As a result of these measures, higher education institutions were initially relatively well protected from the public spending cuts that followed the 2008 financial crisis. Further education colleges did not enjoy the same protections, and were subject to budget and numbers cuts across their programmes, particularly in adult education provision, though some could benefit from the fee reforms for their higher education provision.

There has been a significant period of uninterrupted growth in higher education, particularly in universities – and this growth has allowed universities to fund more research, invest in more buildings, and further their societal mission. The central contradiction is that this period of expansion has coincided with a period of economic stagnation in the rest of the country. It could be that the economy would have been worse without university expansion, or it could be there is no link between university growth and economic growth, or – perhaps more likely – that universities do support economic growth but not as well as they could because of a misalignment between government policy, funding, and incentives in the system.

Winter is coming

The system we have was designed to create the conditions for everyone with the will and capacity to benefit to be able to access their choice of higher education with no upfront costs – a noble aspiration. But just as the wider model of economic growth has come face to face with its downsides, so too has this model of funding and allocating places produced some significant system-level downsides: specifically in public satisfaction with higher education, the diversity and responsiveness of the offer, and the general instability of the system that creates barriers to fixing these issues.

The unsustainability of an home undergraduate funding model, in which students resent the expense of the core tuition fee “sticker price” while higher education providers struggle to cover their costs as the real value of the fee erodes with inflation, are well rehearsed. There is little public appetite for a transfer of public funds into higher education, though many believe it should be cheaper. There are problems with the student maintenance package in England, which falls well short of what students require to cover their living costs. There has also been a systematic inequity between the higher education student finance system which makes provision for student maintenance, and advanced learner loans, which do not – something the LLE should correct.

But the challenges the post-18 sector faces extend well beyond the core funding conundrum.

As the Augar review of post-18 education pointed out in 2019, the incentives in higher education are for institutions to offer courses that are well-understood and popular in the largest part of the market i.e. full-time three year undergraduate bachelors degrees and to a much smaller extent, degree apprenticeships. The current system has fuelled the headline of expansion of young entrants to degree-level qualifications while participation among those over 21, those studying part-time, and those studying sub-degree level qualifications has declined. The funding system is only one part of this picture – there are other underlying issues driving both supply of and demand for particular qualifications – but the broad point is that the system as it is currently configured does not create the conditions for being innovative in post-18 provision either to respond to changing student circumstances, or to employers’ needs.

Moreover, while notionally the current system operates a level playing field, in practice providers have a highly variable capability to operate and flourish in a competitive market. This competitive system is profoundly destabilising for those institutions less able to secure sufficient student numbers year on year to sustain their operating costs. Institutions not geared up to rapidly change their operating models to adapt to changed patterns of student demand – especially against a volatile backdrop of fluctuating international student numbers, eroding unit of resource for UK students, and the Covid-19 pandemic and period of inflation that followed it – have struggled to stay afloat.

This scenario in which popular institutions and courses have been able to expand student numbers, while others have contracted is a feature not a bug of a marketised system, benefiting the students who are able to secure their first choice of institution, including a greater number of students from less advantaged backgrounds who can more readily secure a place at a selective institution, if that is what they want to do. But behind the the headlines of increased choice, as the unit of resource via the undergraduate fee and the additional funding for high cost subjects distributed via the Strategic Priorities Grant have declined in real terms, the sector has seen a relative decline in provision of the subjects that cost more to deliver – subjects that, as Universities UK has pointed out, match closely with the sectors identified as priorities in the industrial strategy, while those that cost less to teach and have broad market appeal, such as business, have expanded.

Of particular concern to any government, but particularly to a Labour government, must be the support for regional institutions with significant public sector education provision. But beyond that risk of teaching, or nursing provision, for example, there is also a wider risk to subject and institutional diversity and continuation of delivery of subject areas with strong regional industrial links that a fully market-led approach cannot correct.

This might be deemed the price to pay for facilitating open student choice. Indeed, acting on the consumer interest over the provider interest is a key tenet of how successive administrations have managed public services more broadly – for example, expanding popular schools, allowing patients to choose their hospital for treatment and growing the most popular ones, and so on. But the higher education sector is not largely like other public sector institutions in that the government does not have the tools to manage market volatility such as forcing mergers or managing orderly institutional closure. As such, the destabilising effect on institutions has a direct knock on effect on the public interest. But nor has this greater matching by student preferences in higher education course and institution choice appear to have resolved chronic skills shortages in the country or addressed some of the ingrained productivity challenges.

Graduates, geography and the labour market

Given that much higher education provision does not relate to specific job roles, it can be hard to make precise claims about the relationship between higher education provision and the labour market. Claims that graduates are not “work ready” are not always very helpful; the definition of “work ready” is too subjective and fails to account for the very different environments and expectations that most graduates experience in education and workplace settings. However, higher education is dogged by claims about the “oversupply” of graduates leading to an estimated one-third nationally of those with graduate-level qualifications occupying jobs that are not currently classified as requiring a degree. The economic returns to a degree can be highly variable depending on the individual’s personal characteristics, subject of study and the sector and geography of an individual’s labour market participation, with patterns of growth in highly-skilled work uneven across the country. And as employer demand for graduates to arrive equipped with specific technical skills increases, higher education provision can sometimes struggle to stay up to date.

It is possible that these challenges arise because students are graduating with the “wrong” skillset from having graduated from the “wrong” subject; in other words, that students in aggregate are making choices only weakly linked to labour markets and/or the qualifications do not adequately prepare them for employment. It is also possible that some industries in some parts of the country struggle to deploy the skills of the workforce that is available to them because of having low access to the graduate labour market, a lack of investment in innovation, or lack of management capacity.

Either way, a wholly student-led approach to picking degree courses and then matching to graduate labour demonstrably isn’t leading to the necessary level of symbiosis between the economy and labour market (regionally or nationally) and its post-18 provision. And if, as the government’s projections indicate, the future economy will depend not only on a ready supply of people who are prepared to deploy general graduate level skills in the workforce, but also to some degree for specific knowledge and skills to be available in specific parts of the country, then the market will need to be shaped accordingly. Skills England’s assessment is that there are “especially strong benefits to be realised by ensuring higher education institutions are even more engaged with local skills needs, as well as those that are strategically important for our country, such as medicine and science.”

Place and provision

An over-focus on competition also has a knock-on impact on the institutional resource and strategic bandwidth of institutional leadership to develop and sustain new partnerships and innovative provision, and undertake “unfunded” activity such as civic and regional development. For many higher education institutions, including FE colleges and specialist providers, such activity is understood as being part of the core mission rather than a bolt-on – but it remains the case that the system we have does not incentivise or even, particularly, support this kind of civic and regional engagement, still less, against a highly competitive backdrop, coordinated co-development of post-18 provision.

To illustrate, a recent study exploring the challenges of a lack of coordination in the post-16 landscape for specific industries from the perspectives of employers, young people, and education and training providers found a wealth of systemic issues in addition to the industry-specific challenges.

The report cites:

- a lack of defined structures for employers and education providers to engage with,

competition between colleges and universities driving prioritisation of student enrolment rather than employer needs, - and for young people, fragmentation in the information, advice and guidance landscape along with baked-in prejudice towards technical and vocational provision.

Finally, the influx of new providers, many without their own degree awarding powers, has led to significant innovation and specialised higher education provision, from Cordon Bleu cookery to interdisciplinary degrees. But it has also led to a rapid increase in franchised and validated provision in which providers without degree awarding powers recruit and teach students and award the degree of another provider, often one that is located many miles away from the validated provision.

Such arrangements are, to an extent, a necessary and legitimate feature of allowing new entrants to the system, but increasingly it’s becoming clear that they can also attract actors whose primary interest appears to be in teaching as many students as possible at the highest possible profit margin, often specifically targeting students with low educational capital from economically underserved areas. Concerns about weak regulation of partnerships and potential fraud in the system have prompted the government to consult on proposals to strengthen oversight of partnership arrangements. Recent data suggests that in the last three years more than £1 billion in tuition fee loans has been paid to providers that not only do not have degree awarding powers but that do not appear on the Office for Students’ register of providers.

The system as it stands therefore has a worst of all worlds approach when it comes to skill provision. There is no effective means of matching labour market needs to student instruction. Providers are not incentivised to do the things that the government believes to be important, like regional growth. And where innovation does exist, the regulatory environment has failed to keep up.

Under the old economic paradigm, the government funded the expansion of traditional higher education as a good in and of itself, and then introduced various alternatives alongside it when the traditional model started to look a bit too abstract or a bit too expensive. Diversity of provision is a strength of the system, as it allows individuals to identify the version of post-18 education that will best suit their needs, but efforts to pursue diversity have led to fragmentation on both the supply and demand side.

Under the new economic paradigm, the government will continue to expand human potential through education and upskilling – that is why it has created Skills England. But rather than relying on the human capital produced to create economic growth, post-18 provision will need to be more closely aligned with wider industrial strategy and growth agendas. This requires something closer to a whole-system approach rather than piecemeal policy reforms.

05

An agenda for the post-16 education and skills strategy and HE reform white paper

The Labour government has made economic growth its number one priority. And it has also indicated through its general election manifesto some of its core ambitions for post-compulsory education provision, including the development of a comprehensive post-16 skills strategy, the creation of the new Skills England arms-length body, transforming selected FE colleges into Technical Excellence Colleges, converting the Apprenticeships Levy into a Growth and Skills Levy, and generally to improve access, raise standards and create a secure future for higher education “to deliver for students and the economy.”

The post-16 education and skills white paper is likely to set out an ambition to shift from a fragmented and competitive sector to a more coherent and coordinated one – as indicated by skills minister Jacqui Smith in a speech to the Association of Colleges conference in November 2024. Plans for reform of higher education will be published as part of that strategy, with policy detail expected on the themes of access, quality, higher education’s contribution to economic growth and regional development, and financial sustainability. The government has also committed to continue the rollout of the planned Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE) which, in its current form, will harmonise the student loan offer for higher education and adult learning above level 4 and make it possible in principle for an individual to register and receive loan finance for modules (initially only in designated technical courses) as well as full courses that lead to a formal qualification

A mountain to scale

The government has set itself a highly challenging task in any fiscal environment, never mind the current one. Even defining a post-16 education “system” – including level 3 A level/T level and their equivalents in schools and colleges, higher education, further education, apprenticeships, work based learning and adult education – is not an easy job. Designing and implementing policy interventions to build towards a more a coherent, efficient post-16 education and training system in England which maximises local and national economic growth, and is fair to all students and learners of all ages and circumstances, regardless of where they live and how they were brought up, feels like the sort of policy challenge designed for the proverbial long grass.

On higher education finance the indicators are that the government will index undergraduate tuition fees to inflation on a rolling basis – but it expects to see significant movement on efficiency, safeguarding of public finances, and delivery of its priorities as the quo for the public quid. There is clearly very little appetite for reform of the core funding model, however unpopular. And any hopes that there might be injections of new public funding to support activity in priority areas are clearly forlorn – as the government has shown in its decisions about cutting and reprofiling the Strategic Priorities Grant and the removal of funding from the vast majority of level 7 apprenticeships. Universities, under the auspices of a Universities UK taskforce have sought to show willing on efficiency and transformation, including pursuing new collaborative models for service delivery and operations, but the recent report of the taskforce’s work indicates that there is only so much the sector can do on its own initiative and to an extent it is looking to government to set out a “vision” around which the sector can convene.

The central policy question is how government can pivot the bits of the post-compulsory education sector that it has little direct influence over towards its core economic mission.

The government could propose relatively modest reforms: encouraging low-key local coordination between providers around access and skills through Local Skills Improvement Plans; wagging fingers on quality and leaning on the Office for Students to “crack down”; and endorsing efficiency efforts (while keeping its fingers crossed that any institutional insolvency can be managed under existing policy frameworks).

But this would be a mistake. As has been argued already, despite the knowledge and skills the post-18 sector demonstrably produces for the public benefit, the system is not in its current state fit for purpose if that purpose is driving economic growth and productivity, and by association raising the quality of life and opportunity for individuals across the country. Simply funding more of it has not led to the productivity gains that might be expected if the solution was simply about increasing higher-level skills in the general population.

While the reality may be that the government’s scope for reform at pace is limited, it should not be shy about setting out a bold agenda for a reformed higher education sector and defining some steps towards it. Adverse economic circumstances nevertheless offer an opportunity to create a new kind of higher education policy agenda – one that is neither entirely top-down from the state, nor left to the vagaries of “market choice” but one that builds in mechanisms for co-design and co-delivery from the outset and in doing so establishes a new civil compact between the state, higher education providers, and the public.

Under the auspices of a new industrial strategy, post-18 institutions will need to more closely link their activity to the new approach to economic growth. This could potentially have three different facets:

- Housing and developing expertise on their regional economies and labour markets to inform growth agendas

- Demonstrating responsiveness in education provision to specific labour market shifts and growth plans

- Strategically intensifying research, innovation and knowledge exchange activity in core areas of alignment to industrial strategy and growth plans

While arguably any single higher education institution could point to activity in at least one of these areas, the prize for national policymakers will be to harness the collective knowledge and practice of the sector to enable all of this activity to be more coordinated and strategic, and more accountable to regional stakeholders and the public.

The upcoming strategy for post-16 education and skills and higher education reform is the opportunity for the government to set out its aspirations for a new system, even if every element of that system can’t be achieved right away – creating space for institutions to step up individually and collaboratively to use the knowledge and expertise they hold to develop answers to some of the policy challenges.

Compass points for reform

To achieve this, we propose that the government must, in its post-16 education and skills and higher education reform white paper, set out the government’s aspirations around five core policy themes:

- Understanding the landscape: so that there is a framework underpinned by data and evidence for regional growth planning incorporating skills and innovation that regional authorities, especially those with lower maturity, are not obliged to reinvent the wheel in developing regional economic growth plans.

- Developing regional education and skills brokerage systems: so that employers can have greater visibility of the knowledge and skills pipeline, and prospective students can benefit from greater coordination – with the potential for the emergence of innovative models of delivery including credit transfer arrangements

- Cooling the student recruitment market and supporting collaboration: leaving space for student choice while reframing incentives towards economic growth, with the longer term aim of reducing the risks of innovation

- Killing the academic/vocational divide: reducing the complexity of the qualification landscape and opening up opportunity for institutions to design education that meets labour market and student needs

- Financing and facilitating transformation

Understanding the landscape

The policy landscape is littered with failed regional economic growth initiatives from regional development agencies in the New Labour years, to local enterprise partnerships under the coalition government, to the “levelling up” agenda. Former Prime Minister Tony Blair has said that one of the lessons should be about the critical relationship between universities and economic growth:

If you look at those things that really drive economic development, I think the position of cities and universities are really important. We did a lot, in fact, to revive a lot of the cities. Cities like Newcastle and Liverpool, Glasgow, Cardiff…all of these places became much more interesting, much more vibrant places. But we didn’t really, until the end, start to understand the absolutely crucial relationship that was starting to develop between universities and economic development, which I think today is absolutely central.

Higher education institutions are obvious hubs for knowledge about economic growth in their region generally, and the role of skills and innovation in particular. Investing in knowledge about “what works” for differing regional economic ecosystems should reap significant dividends both in catalysing activity and ensuring it is monitored and evaluated to draw lessons for the future.

Following publication of the industrial strategy, the government should conduct or commission a review of the knowledge landscape for regional economic growth, mapping both existing expertise and the data environment informing regional economic growth plans against national sectoral and spatial priorities, and setting out a plan to address gaps.

In order to make this more regional approach work there should be a modest regional growth knowledge fund to which groups of regional providers and their partners can apply to establish regional growth insight centres with direct links to devolved authorities, on the assumption that the more efficient allocation of provision will be a net cost saving.

Developing regional education and skills brokerage systems

In Scotland, the regional tertiary pathfinders pilot projects demonstrated what can be achieved with a very little money and a lot of good will – simply bringing education institutions together with employers and regional stakeholders to begin to map the education and labour market landscape and explore the potential for closer alignment in the spirit of action research led to all kinds of learning and new activity.

England’s regional governance is arguably not yet mature enough to consider a funding devolution and commissioning framework for education and skills at every level, but it should be possible under the devolution framework for every region to have a “table” around which diverse education providers, employer representatives and other regional stakeholders “sit” that is explicitly tasked with:

- better understanding the alignment between post-18 education and the labour market to inform dialogue with Skills England and government around regional skills and labour market priorities

- creating a joined-up knowledge base about available curriculum pathways that can underpin provision of information, advice and guidance to prospective students and signposting for employers

- brokering proposals with education institutions for enhanced coordination and streamlining of provision

The Devolution Bill should make provision for mayoral combined authorities to convene a post-18 education and skills provision group with a diversity of provider and industry representation that can draw on the insight from regional growth insight centres to develop post-18 pathways, provision and partnerships. These groups could initially propose business cases for reprofiling of funding but over time could be given direct commissioning powers and/or direct injections of public funding to catalyse new provision aligned to national or regional economic growth priorities.

The forthcoming HE reform white paper and skills strategy should also set out an ambition for a regional access approach that sets collective targets for post-18/L4 or above participation, that is qualification agnostic and identifies key under-served groups across the education system that can guide shared priorities and collective action. The exception should be where an historically selective university has a published entry tariff above a defined level, it needs to be held to access targets for the recruitment of under-represented students.

Cooling the market and supporting collaboration

Competition can be healthy, but there are downsides to a system driven entirely by student choice. While institutions may offer lots of positive noises about collaboration and coordination, the calculus of survival may yet encourage – or force – them into a competitive posture. Yet the prospect of reimposing universal student number controls or central labour market planning is also unpalatable, given the complexity of the system and the arbitrariness of freezing it in its current state.

On the punitive side the government could explore a more robust regulatory approach to managing full-time home student number growth, placing temporary but binding limits on institutional growth rates, with a requirement to produce a business case for plans to breach that cap based on the industrial strategy’s priorities or in exceptional circumstances such as the acquisition of another provider. While a measure like this would probably not be welcomed by the sector, it could bring a measure of stability and potentially allow for more robust financial planning. Closer oversight of franchised arrangements could form part of this measure, with unregistered providers equally bound by growth restrictions unless there is a clear rationale for new provision – for example, to address a higher education “cold spot” or meet the need for emerging specialist provision in a particular industry.

On the incentive side, the government should designate national priorities where it believes post-18 institutions can collaborate, convene, and drive change. This should be a rolling set of priorities which are funded, through application and business cases, that cover both enormous internal challenges like training large cohorts of students in advanced digital skills, and efficiency measures like supporting collaboration in teaching design and delivery. The programme should simultaneously allow structured funds that ease the flightpaths for providers to make sensible choices on collaboration to ease cost burdens while incentivising targeted work on regional and national economic needs.

Within a calmer market environment there should still be a role for a regulator that is concerned with the material delivery of higher education via a concern for quality, value for money, and students’ interests. However, the Office for Students is not currently configured to be empowered to shape the market as well as regulating provision. Either the regulator will need to be reconfigured so as to be a more powerful convenor of activity or its regulatory role more tightly defined and the convening power directed elsewhere. Skills England could potentially be empowered to create policy space for developing the coherence that is sought across higher and further education, apprenticeships and adult learning.

Killing the academic/vocational divide

Fragmentation of the qualification landscape does not serve students, institutions, or employers. For the last decade or so, government ministers have sought to promote participation in higher technical qualifications and degree apprenticeships, with limited success. Degree apprenticeships in particular are arguably a good example of policy failing to meet the expectations that were set for it. UCAS research with the Sutton Trust found that 40 per cent of prospective undergraduate students are interested in apprenticeships – far more than the volume of actual apprenticeship opportunities – indeed the main reason given for not taking up an apprenticeship was that there was not a suitable one available. That research also uncovered significantly worse experiences of finding information about and applying for apprenticeships, and a continued belief that degree apprenticeships are much less prestigious than traditional degrees.

From a student perspective, it doesn’t seem especially radical to suggest that for any post-18 applicant considering study at level 4 or above it should be possible to tap into diverse choices not only of different kinds of providers and subject areas but varied and flexible modes of study. Imagine if instead of the choice of a “degree” or a “degree apprenticeship” it was possible, within defined limits, to dial up or down the ratio of classroom to workplace delivery or the ratio of in-person to online delivery; to compress or extend the number of credits acquired in a given timeframe; or to be offered the opportunity to study with different kinds of provider at different points in a course – all within a single funding and regulatory framework.

The ongoing rollout of the LLE should open up the opportunity to think about the kinds of provision that the government wants to fund as well as the funding delivery mechanism. Within a single framework there could be programmes that are designated as eligible for funding via the new growth and skills levy while others require students and/or employers to fund through direct financing or student loans. This would give the government the opportunity to incentivise strategically important provision, while enabling institutions to design qualifications in a way they think will best meet the needs of students and employers in as frictionless a way as possible.

The post-16 skills and education strategy should indicate a plan to move to a single qualification framework for post-18 provision that allows for a sliding scale between work and scheduled learning, encompassing what we currently think of as higher and degree apprenticeships, higher technical qualifications and full degrees. Post-18 providers, in partnership with employers as appropriate, should be able to design qualifications within that framework that best meet their needs and that of the students they aim to attract. Under the auspices of a single qualification framework regulation of quality, students’ rights and interests and monitoring of student outcomes should begin to be brought together into a single regulatory framework.

The government should commission a tightly focused review on the delivery of qualifications other than the “core” Level 6 Bachelors provision – specifically, level 4 and 5, and level 7 provision.

- Level 4 and 5 qualifications, like higher technical qualifications or higher apprenticeships, provide the skills that employers need in technical roles and also form a gateway to higher qualifications.

- Level 7, masters level qualifications, are not only an enormous attractor of international students but support the higher level knowledge and skills ideal for economic innovation and regional growth.

The review of level 4 and 5 should focus on how funding arrangements support a diversity of provision and a diversity of pathways both into skilled work and further learning either immediately or in future. The review of level 7, particularly given apprenticeship reform and the defunding of level 7 degree apprenticeships, should look at how education institutions can be supported to offer programmes that align to labour market needs, how learners could benefit from more flexible provision, and the ways in which the sector can maintain its global competitive advantage. More diverse entry pathways and more labour market alignment and flexibility in level 7 programmes should also incentivise providers to adapt their work at core level 6.

Financing transformation

Everybody knows there is no money – and what little money there is already is subject to cuts and reprofiling. But that means that both government and post-18 education providers need to be more creative about how to fund transformation. A number of UK banks already have deep relationships with higher education and would be open to discussions about a role for government in creating the conditions that would enable banks to consider supporting higher education transformation with private finance. The government should acknowledge the costs of transformation and commit to exploring with the sector sustainable options for funding it.

More controversially, the government should not shy away from signalling what it would like to fund if economic circumstances improve. Throughout this paper there are suggestions for modest injections of public funds to catalyse and incentivise strategically important activity in the post-18 sector. A signal from the government about its priorities and aspirations could help to galvanise discussions now, even if the available funding pot is constrained. As institutions make difficult decisions about what is sustainable, and continue to reform their operating models, a clear steer from government about its priorities for post-18 education will help to guide those decisions.

06

Conclusion

Higher education providers, of all kinds, are already doing significant work to make their regions more productive and more prosperous. There is no doubt that the majority of staff in those institutions see their success as bound up with the life chances an education offers their students. The challenge is that the way higher education is configured gets in the way of providing an education which more clearly meets regional and national economic priorities.

Higher education providers hold significant knowledge and experience that could be deployed in the service of policymaking. The vast majority in our experience are committed to enhancing their impact on lives, communities and the world. But the reality is that at times of financial pressure their ability to surface and apply their knowledge and filter changes through their organisation will depend on the ability they have to do so. While many are in the process of transforming their operating models, there is still a significant degree of exposure to shifts in international recruitment. And the administration of regulatory requirements, data collection and return, portfolio management, student registration and timetabling, and statutory duties on things like equality and freedom of speech are very hard to streamline to the degree that it makes a significant difference to the bottom line.

For these reasons, effecting change requires the government to set out an agenda and priorities for higher education, and the policy to back it up. But that agenda will be much more powerful if it is framed as a process of co-development and co-learning, driven by engaged communities and public stakeholders as much as by government or by providers themselves. Higher education providers do not exist in a vacuum. There needs to be a new settlement that aspires to the inclusion of multiple types of provision, qualification, institution, and student, ambitious for economic growth and regeneration, and that builds collective shared accountability for delivering it.

References

Department for Business and Trade green paper, Invest 2035: the UK’s modern industrial strategy, October 2024.

Department for Education, Labour market and skills projections 2020 to 2035.

Department for Education, Review of post-18 education and funding independent panel report, May 2019.

Department for Education, Skills England: driving growth and widening opportunities, September 2024.

Katherine Hill, Matthew Padley & Josh Freeman, A minimum income standard for students, HEPI, May 2024.

Tristram Hooley, “A mixed bag: employer perspectives on graduates skills” Prospects Luminate, March 2021.

Institute for Fiscal Studies, The Conservatives and the economy, June 2024.

Shitij Kapur, UK universities: from a triangle of sadness to a brighter future, King’s Policy Institute, November 2023

Mark Leach, “It’s time to take a closer look at an ‘opaque corner’ of higher education,” Wonkhe, June 2023.

Office for Students, Improving opportunity and choice for mature students, May 2021.

ONS Local, Employed graduates in non-graduate roles in parts of the UK 2021 to 2022, August 2023.

Public First Public attitudes to tuition fees, October 2023.

Rachel Reeves, A new business model for Britain, Labour Together, May 2023.

Rachel Reeves, Mais lecture, March 2024.

James Robson et al. From competition to coordination: rethinking post-16 education and training in the UK. Industry case studies, SKOPE and the Education Policy Institute, April 2025.

Universities UK, President’s address to conference, September 2024.

Universities UK, Supply and demand for high-cost subjects and graduate progression to growth sectors, May 2025.

Michael White, “No retreat on student fees, Blair warns,” The Guardian, December 2003.

David Willets, How to do industrial strategy: a guide for practitioners, Resolution Foundation, April 2025.

Xiaowei Xu, The changing geography of jobs, Institute for Fiscal Studies, November 2023.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following for their contributions to this paper

Professor Andy Westwood

Jess Lister

Mark Leach