The cashpoint campus comeback franchising, fraud, and the failure to learn from the FE experience

A policy paper on the chronic lack of institutional memory from regulators and government and the urgent need for cross-sector learning

Date:

Author:

01

Executive summary

The higher education sector is mired in a franchising crisis that mirrors – almost precisely – scandals that rocked further education a decade ago. Over £1 billion in tuition fee loans has flowed to unregistered providers over the past three years, while fraudulent activity, exploitative recruitment practices, and catastrophic student outcomes proliferate. The National Audit Office has uncovered organised crime, ghost students, and continuation rates as low as 66 per cent at some franchised providers.

This paper argues that the government’s response represents a troubling case of institutional amnesia. In 2020, the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA) implemented comprehensive reforms to FE subcontracting that addressed identical issues – geographical distance, volume controls, whole programme restrictions, and enhanced oversight. These reforms worked. Yet, the Department for Education (DfE) is now proposing to reinvent the wheel for higher education, with implementation not set to begin until 2026 and full effect not until 2028. This is even harder to understand when you consider that ESFA was recently absorbed back in to DfE – it appears that all learning has been lost in the process.

The central challenge is not whether reform is needed – it manifestly is – but why proven solutions from one part of the tertiary sector cannot be immediately adapted for another. This paper demonstrates how reforms made in FE could be translated to HE within months, not years, potentially saving hundreds of millions in misallocated public funds and protecting tens of thousands of vulnerable students from educational malpractice.

02

The franchise explosion: Déjà vu all over again

When, earlier in 2025, Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson declared the current situation “one of the biggest financial scandals in the history of our universities sector,” she was both right and wrong. Right about the scale – wrong about the novelty.

As early as 2014, investigations uncovered Romanian builders trafficking people to the UK to fraudulently claim student loans, and colleges dubbed “the ATM” where students collected their £11,000 and vanished.

The numbers tell the story. Student enrolments at franchised providers more than doubled from 50,440 in 2018–19 to 108,600 in 2021–22, reaching over 138,000 by 2022–23. In 2023–24 alone, nearly £450 million in tuition fee loans went to students at providers not registered with the Office for Students (OfS). Private providers report profit margins exceeding 50 per cent – companies house records show that one turned over £73 million with education costs of just £17 million, pocketing a 53 per cent pre-tax profit.

These are not the specialist providers or innovative upstarts that former universities minister Jo Johnson envisioned when comparing validation requirements to “Byron Burger having to ask permission of McDonald’s to open up a new restaurant.” Instead, we see cookie-cutter business degrees delivered from converted office blocks, sold door-to-door with promises of “£15,000 funding today” and attendance requirements of “just two days a week.”

@eduexukReady to Study in the UK and Get Financial Support If you have UK/EU citizenship or Pre-Settlement/Settlement/Refugee status, you can access government-funded courses with up to £15,000 in maintenance funds The best part: ✅ Study only 2 days a week ✅ Apply with/without qualification ✅ No age limits—everyone is encouraged to apply! ✅ FREE expert guidance for your applications and funding! Contact us to begin! 𝐄𝐃UEX………………. 07777 719 330 contact@eduex.co.uk www.eduex.co.uk 117 Whitechapel Road, 2nd Floor London, E1 1DT #uk #ukeducation #founding #undergradute #study #studyinuk #bussinessmanagement #healthsocialcare #law #accounting #accountingfinance #project #projectmanagement #govt♬ original sound – EduEx

The targeting is cynical and precise. In 2022–23 and 2023–24, over 65 per cent of students eligible for student finance on subcontracted courses were from nationalities where English is not the first language – particularly Romanian nationals and those with pre-settled status. The Student Loans Company reports thousands of students who receive maintenance loans but never draw down fee loans – a clear indicator of enrollment purely for cash access. In 2023–24 alone, a Freedom of Information request to the Student Loans Company revealed that 10,582 students in England received first instalments of maintenance loans without any tuition fees being paid.

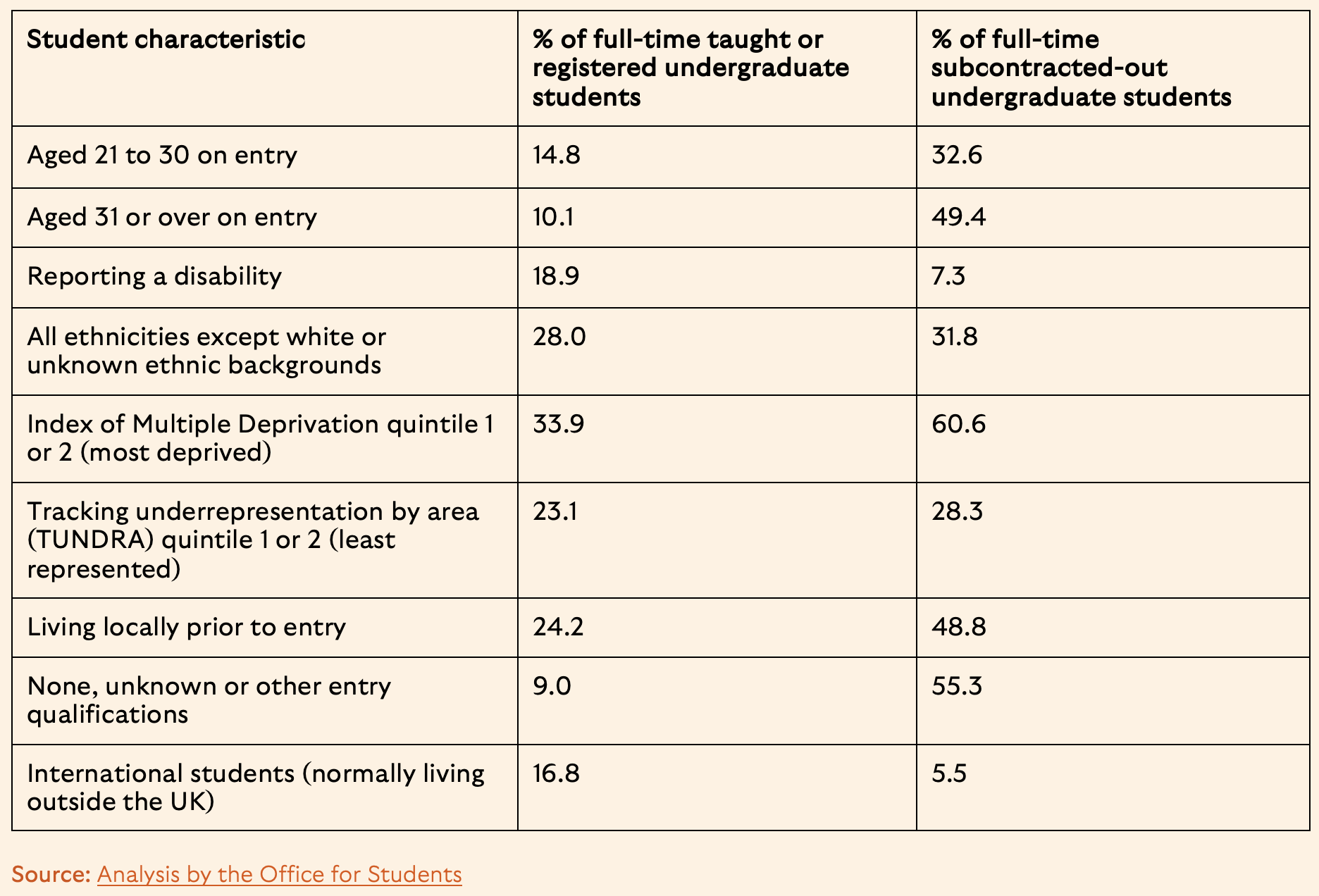

The human cost is significant. Of nineteen franchise partnerships examined by OfS, only two met the minimum 80 per cent continuation threshold. At one large partnership, just 66.7 per cent of students continued to their second year. These are predominantly students from disadvantaged backgrounds – 62 per cent from high deprivation neighbourhoods, compared with 40 per cent across all providers. Nevertheless, while franchise provision shows high rates of economic disadvantage, the proportion reporting disabilities is suspiciously low – suggesting either poor support or active discrimination in recruitment.

03

The anatomy of exploitation

Understanding how this crisis developed requires examining the ecosystem that enables it. At every level, perverse incentives align to exploit students whilst extracting maximum profit from public funds.

The ghost student phenomenon: NAO investigations revealed students who exist only on paper – enrolled to trigger loan payments but never attending classes. In one case, a university discovered the “majority” of students at a franchise partner weren’t producing their own assignments. When challenged, just six per cent responded, with evidence suggesting even these were coached. The Student Loans Company identified 3,563 suspicious applications worth £59.8 million linked to organised crime. These aren’t isolated incidents but systematic fraud.

The profit pipeline: The financial flows reveal the scandal’s architecture. Universities receive 12.5 to 30 per cent in franchise fees. Private providers then extract profits of 30 to 53 per cent. Domestic agents – a largely invisible industry until recently – take commissions for each student recruited. By the time money reaches actual education, perhaps 30 pence of each pound remains. One provider showed a £73 million turnover with just £17 million spent on education – the rest vanishing into administration and profits.

The absence of student voice: Also telling is the absence of independent student representation at franchise providers. There are rarely students’ unions, few course representatives with real power, and little independent advocacy. When students at one college investigated by OfS raised concerns in meetings, inspectors appeared to tick the “student engagement” box based on process not outcomes. Students don’t know their rights, can’t access support, and have no collective voice. This isn’t accidental – it’s designed to prevent challenge to the business model.

The lag that enables: Perhaps most pernicious is how outcomes-based regulation fails when growth is exponential. Continuation rates are measured over years – providers can recruit thousands before poor outcomes become visible. By then, owners have extracted millions, students have accumulated debt, and new providers have emerged to repeat the cycle. The system’s rear-view mirror approach enables exploitation by design.

04

Why memory matters: The FE precedent

What makes this crisis particularly galling is that further education faced – and largely solved – identical problems. Between 2014 and 2020, the ESFA witnessed widespread abuse of subcontracting arrangements – provision delivered hundreds of miles from lead providers, excessive management fees, students enrolled solely to access funding, and quality disasters hidden behind commercial confidentiality.

The parallels are uncanny. Where universities retain 12.5 to 30 per cent of fees, FE providers were skimming similar percentages. Where London-based companies now recruit students with pre-settled status for business degrees, FE saw similar targeting of vulnerable communities for basic skills provision. Even the ghost student phenomenon – learners who existed only to trigger funding – plagued both sectors.

The ESFA’s response was comprehensive and effective. In 2020, following CEO Eileen Milner’s stark warning in 2019 that “abuse of subcontracting will only ultimately serve to limit access for learners,” the agency launched a consultation that resulted in sweeping reforms.

These included:

- A requirement for governing bodies to approve and publish a clear educational rationale for any subcontracting

- Prior approval for geographically distant provision

- Volume controls limiting subcontracting to 25 per cent of income

- Restrictions on whole programme subcontracting

- Direct contractual relationships with third parties

- A single set of funding rules across all provision

- Development of an externally assessed management standard

Crucially, these reforms were implemented within eighteen months, with most taking effect from the 2020–21 academic year. They worked. Subcontracting volumes fell, quality improved, and the most egregious providers exited the market. The Association of Colleges now reports that where subcontracting remains, “models are generally strong and reflective of local demand.”

05

Learning from FE’s experience: strengths and gaps

Four years after implementation, FE’s reforms show both successes and shortcomings that HE must learn from.

What worked well

Board-level accountability transformed franchising from a finance office decision to a governance priority. As college board minutes now demonstrate, subcontracting is a standing compliance item requiring active oversight. The requirement for published rationales forced transparency – no longer could providers hide dubious arrangements behind commercial confidentiality.

The prospect of a direct Ofsted inspection for large subcontractors changed behaviour. AELP’s Simon Ashworth notes that clearer lines of responsibility improved both quality and financial flows. The 20 per cent fee retention expectation, while not statutory, created a benchmark that shifted sector norms.

Where gaps remain

Nevertheless, implementation revealed weaknesses HE must address. The DfE customer forum shows ongoing confusion about audit requirements – practitioners report 12-week ESFA response times and ambiguity about filing requirements. And ESFA’s own 2023–24 assurance guide reveals that routine audits check funding-rule compliance but “do not check for compliance with the subcontracting standard” – the headline reform sits outside regular oversight.

Administrative burden fell heavily on small specialists. FE Week’s warnings about distance caps putting rural and SEND providers “out of business” proved prescient. The lack of a statutory fee cap means some providers still retain excessive percentages if they can “evidence value.” Regional variation adds complexity – devolved authorities interpret standards differently, creating what one multi-campus principal called “a compliance postcode lottery.”

06

Why DfE’s current proposals fall short

The Department for Education’s consultation proposals, while acknowledging the crisis, represent a fundamentally flawed approach that misunderstands both the scale and nature of the problem.

The centrepiece – requiring providers with over 300 students to register with OfS by 2028 – fails on multiple grounds.

The timeline is inexcusable: Waiting until 2028 for full implementation borders on regulatory negligence. The current growth trajectory suggests over 200,000 students will pass through franchised provision before controls take effect. At current dropout rates, that represents 60,000 students failing to continue – each saddled with thousands in debt. The NAO has already identified organised crime in the sector – waiting four more years while criminal enterprises operate with impunity defies comprehension.

This timeline also contradicts the government’s own rhetoric about urgency. As Phillipson herself noted: “This problem has been growing and has been highly concentrated in a small number of providers in the sector.” If the problem is both growing and concentrated, delay makes no operational sense.

The threshold is too high: Setting the bar at 300 students ignores how damage accumulates. A provider teaching 250 students at a 66 per cent continuation rate still represents 85 failed students annually. Across multiple such providers, the aggregate harm is substantial. FE learned this lesson – even smaller providers can cause significant damage when operating at scale across multiple partnerships.

Registration alone won’t solve systemic or incentives issues: OfS registration is necessary but insufficient. As cases have demonstrated, registered providers can still engage in academic fraud, aggressive recruitment, and poor practice. The register was never designed to handle profit-driven providers operating at the margins. Without addressing the fundamental incentives – the extraordinary profits available from minimal delivery – registration merely legitimises current practice.

OfS itself has acknowledged capacity constraints, temporarily closing new registrations in 2024. Adding hundreds of franchise providers to an already strained system invites regulatory failure.

The innovation fallacy: DfE’s approach fundamentally misunderstands innovation. Small providers can indeed innovate – Channel 4 demonstrates this principle in broadcasting, commissioning ground-breaking content without owning production facilities. But Channel 4 doesn’t claim every independent production company needs a broadcast licence.

The parallel in HE should be clear – innovative small providers can create excellent educational experiences through partnership without needing full institutional infrastructure. Forcing them all to become mini-universities misses the point entirely.

The proposals ignore the agent problem: DfE’s consultation barely touches the domestic agent industry despite its central role in driving inappropriate recruitment (notwithstanding repeated promises of action dating back to January 2024). Waiting for April 2025 just to make the Agent Quality Framework mandatory – and even then only for international recruitment – shows a failure to grasp how these operations work.

Domestic agents operating on commission, targeting vulnerable communities, using misleading advertising on TikTok and in shopping centres, are the sharp end of exploitation.

No real powers over financial arrangements: The proposals say nothing about the financial splits between universities and franchise partners. When universities cream off 30 per cent and franchise providers still make 50 per cent profits, simple mathematics reveals how little reaches actual education. Without transparency requirements or caps on profit-taking, registration merely provides official blessing for extraction.

The geographic loophole remains: Requiring registration doesn’t address the fundamental absurdity of students registered in Canterbury studying in London, or students from a university in Leeds taught in Birmingham. The fiction that meaningful oversight can occur across such distances will persist. FE’s “one hour by car” rule recognises practical reality – universities cannot easily monitor provision hundreds of miles away, and should be required to demonstrate more clearly that they can if proposing to do so.

Validation as escape route: Perhaps most critically, DfE’s proposals may accelerate a shift from franchising to validation arrangements. If franchise partners must register with OfS, they might instead seek validation – where students register directly with them while receiving awards from universities. This creates even less university oversight whilst maintaining the prestigious brand. The proposals risk pushing problems into an even murkier corner.

07

The political economy of forgetting

The failure of previous governments to apply FE’s lessons to HE reveals deeper pathologies in educational policy-making. Three key factors explain why so much has been forgotten:

Sectoral silos: Despite rhetoric about a unified tertiary sector, FE and HE occupy different policy universes. They have different regulators, different funding mechanisms, and crucially, different teams within DfE. Hard-won lessons in one sector rarely cross the divide. This artificial separation enables identical problems to be treated as novel challenges requiring years of consultation and delayed implementation.

The cultural divide between sectors compounds structural separation. HE policy-makers often view FE as fundamentally different, ignoring that students, providers, and fraudsters move seamlessly between sectors.

Regulatory capture: The HE franchise boom benefits powerful interests. Universities facing demographic cliffs and frozen fees find franchising an attractive revenue stream. Private providers and their investors – including some with remarkable political connections – profit handsomely.

The domestic agent industry, invisible until recently, depends entirely on current arrangements. These interests have successfully framed rapid reform as threatening widening participation, despite evidence that franchise provision often fails the very students it claims to serve.

The innovation illusion: Since the 2011 and 2015 white papers, policy-makers have confused market entry with innovation. The narrative that regulatory barriers stifle new providers offering radical alternatives has survived despite minimal evidence.

Dyson, and NMITE (the New Model Institute for Technology and Engineering) represent genuine innovation; thousandth iteration business degrees in converted offices do not. Yet fear of hampering “innovation” paralyses necessary regulation.

08

The cost of delay

DfE’s current consultation proposes requiring franchise partners with over 300 students to register with OfS. Implementation would begin in April 2026, with first decisions in September 2027 for the 2028–29 academic year.

This leisurely timeline ignores urgent realities:

Financial haemorrhage: At current growth rates, over £2 billion in public funding will flow to unregistered providers before controls take effect. Much will fund provision with continuation rates below 70 per cent, meaning hundreds of millions in loans for students who never complete their courses. The maintenance loan fraud alone – with over 10,000 students annually receiving cash but no tuition – represents tens of millions in direct losses.

Student harm: Tens of thousands more students – predominantly from disadvantaged backgrounds – will be recruited through misleading advertising into programmes with minimal oversight and poor outcomes. Each cohort that enters before reform represents thousands of individual tragedies: debt without degrees, promises without prospects.

Sector reputation: Every scandal further erodes public confidence in higher education. The Sunday Times’s “walk-in degrees” headline joins a litany of negative coverage that tars all universities with the franchise brush. Delay amplifies reputational damage that affects even excellent providers.

Regulatory credibility: OfS was established partly to prevent repetition of “cashpoint college” scandals. Its failure to act decisively undermines confidence in risk-based regulation. When the regulator’s “boots on the ground” take years to march anywhere meaningful, the entire regulatory philosophy comes into question.

09

The translation challenge: From FE to HE

This paper argues that ESFA’s reforms, enhanced by lessons from implementation, could transform HE franchising within months. The core principles remain sound but require strengthening in key areas:

Educational rationale and governance

The FE requirement for boards to approve and publish a rationale for subcontracting addresses precisely the governance failures OfS has identified. According to Advance HE, universities’ audit committees have been rather too sanguine – effective oversight of contractual arrangements “had proved a challenge” for many governors, a common concern from whom was receiving the right kind of information in sufficient detail to give them “confidence in any subcontractual arrangements.”

Requiring a published rationale would force institutions to justify why a provider in the North West needs partners in London, or why some franchise to providers whose continuation rates languish twenty percentage points below campus provision.

However, HE must go further. Boards must not only approve rationales but also review them annually against outcomes data. Where franchise provision consistently underperforms campus delivery by more than 10 percentage points on any key metric, partnerships must be terminated within 12 months.

Each provider should have to have a published policy on subcontracting, and it should include the rationale for subcontracting provision. It must enhance the quality of the offer, and providers should be explicitly informed that they must not subcontract delivery to meet short-term funding objectives.

That enhanced quality would have to hit one or more of the following aims:

- enhance the opportunities available to learners

- fill gaps in niche or expert provision or provide better access to training facilities

- support better geographical access for learners

- support an entry point for disadvantaged groups

- support individuals who share protected characteristics, where there might otherwise be gaps

Financial probity

Here we must go beyond FE’s approach. Universities must neither profit from nor subsidise franchise arrangements – fees should reflect actual costs only, with full transparency required. This cost-recovery principle removes perverse incentives for expansion whilst ensuring proper oversight isn’t undermined by financial dependence.

Providers should have to set out their full range of fees retained and charges that apply including:

- funding retained for quality assurance and oversight

- funding retained for administrative functions such as data returns

- funding retained for mandatory training delivered to subcontractor staff by the directly funded provided

- clawback for under delivery or other reasons

- how the provider will determine that each cost claimed by a subcontractor is reasonable and proportionate to the delivery of their teaching or learning and how each cost contributes to delivering high quality learning

Provider profit

Further Education is not the only part of the Department for Education where learning could be found. The Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill represents a significant shift in how government approaches profiteering – its Clause 15 creates a regulatory framework that establishes the legal mechanism to introduce profit caps should market interventions fail.

The parallels between social care and HE franchising are striking. Local authorities struggle with private providers extracting excessive profits from children’s homes, and care home sector research reveals how providers extract value through complex corporate structures, with concern that the largest for-profit providers taking £15 of every £100 received through profit, rent payments, directors’ remuneration, and interest payments – double the rate of smaller providers.

Similar patterns are present in HE franchising, where opaque financial arrangements obscure the true cost of provision and the destination of student fees. The practice of charging high interest rates on intercompany loans, identified as hidden profit extraction in care homes, also appears in various forms across franchised HE provision.

Adapting the approach in the Bill would involve requiring all for-profit providers delivering franchised higher education to register directly with the Office for Students. The framework would grant the Secretary of State powers, through OfS, particular types of mandatory financial reporting to surface true leakage – and would also give the SOS the power to impose profit caps specifically on for-profit franchised providers, international pathway operators, and private training providers delivering under university franchise agreements.

Geographical controls with flexibility

ESFA’s “one hour by car” principle for FE subcontracting directly addresses the distance problem. The proliferation of London-based providers serving students registered at universities hundreds of miles away makes a mockery of place-based education. Prior approval for distant provision – already operational in FE – would end the fiction that educational oversight can be effectively maintained from Canterbury to Canary Wharf.

Nevertheless, geographical controls should accommodate legitimate exceptions. The specialist provision linked to an area of expertise held by the main provider, specialist provision for students with particular disabilities, and genuinely innovative partnerships deserve consideration. The key is shifting the default from permissive to restrictive – proximity unless justified, not distance unless challenged.

Volume restrictions while recognising innovation

The FE sector’s 25 per cent cap on subcontracted provision (with a trajectory towards 10 per cent) offers a ready-made solution to universities becoming mere “badge providers.” When institutions teach more students through partners than on their own campuses – as several now do – questions about institutional identity become urgent. A phased reduction would allow adjustment whilst preventing further expansion.

However, we must create space for genuine innovation. A separate “innovation track” for truly novel provision (verified by external review) could exceed limits. This protects quality whilst enabling genuine advancement – not the thousandth business degree but actual educational innovation.

Programme integrity with nuance

FE’s restrictions on whole programme subcontracting recognise a fundamental truth – students who never set foot on campus, never meet university staff, and never access university facilities are not meaningfully students of that university. The requirement for prior approval of such arrangements would end the most egregious examples of distance franchising.

Yet implementation must avoid FE’s administrative tangles. Clear criteria, fast-track processes for established quality providers, and recognition of blended models where students access both sites can maintain standards without strangulation.

Providers should be told that they must only use subcontractors for delivery of the provision if they have staff with the knowledge, skills, and experience to successfully select subcontractors in line with the requirements of the funding rules, contract with and actively manage those subcontractors, and that those charged with governance determine the subcontractors as being of high quality and low risk to public funds.

There should be standard terms that have to be included in contracts. They would have to list the services provided and the associated costs for doing so, with specific costs for quality monitoring activities and specific costs for any other support activities offered broken out (with their contribution to the delivery of high-quality learning noted).

Subcontractors should have to agree to give OfS access to their premises and to all documents related to their subcontracted delivery, have to provide student data, and must provide sufficient evidence to allow the subcontracting provider to assess performance against OfS’ regulatory framework.

Student voice and protection

FE’s reforms didn’t adequately address student representation – a gap HE must fill. Every franchise arrangement must include funded student advocates, clear complaints procedures aligned with OfS B conditions, and annual student surveys with response rates above 50 per cent.

Results must be published separately from campus provision – no more hiding poor satisfaction in aggregated data. There should be an expectation that the subcontracting provider’s students’ union will play a role in working with students at the provider to assess quality and support students with complaints.

OfS must also publish provider-level data for all franchised-to organisations, regardless of registration status. If a provider teaches 200 students across multiple partnerships, aggregate performance should be visible. Transparency drives improvement.

Perhaps most critically, HE must address the lag problem that bedevils outcomes-based regulation. Monthly data submissions on recruitment, attendance, and early warnings can trigger intervention before thousands accumulate debt at failing providers. FE’s experience shows annual reporting enables problems to metastasise – HE must do better.

10

Recommendations: A comprehensive reform package

Learning from both FE’s successes and shortcomings, this paper proposes a phased implementation of proven reforms, enhanced by four years of operational experience. These recommendations prioritise immediate student protection while building robust long-term oversight.

1. Emergency Measures (Immediate – by January 2026)

Freeze and investigate existing arrangements:

- Impose moratorium on new franchise partnerships exceeding 50 students pending reform implementation

- Trigger immediate OfS investigations at partnerships with continuation rates below 70 per cent

- Establish emergency intervention powers where organised fraud is suspected

- Require all current partnerships to submit monthly data on recruitment, attendance, and early progression indicators

End commission-driven recruitment:

- Ban domestic agents from receiving per-student recruitment commissions

- Make Agent Quality Framework mandatory for all recruitment (not just international)

- Require full disclosure of agent relationships and payments in partnership agreements

- Implement “cooling off” periods preventing students from re-enrolling solely to access maintenance loans

2. Governance and Educational Rationale (April 2026)

Board-level accountability:

- Mandate governing body approval of all franchise arrangements with published educational rationale

- Require annual review of rationales against outcome data, with automatic termination where franchise provision underperforms campus delivery by >10 percentage points on key metrics

- Make subcontracting oversight a standing compliance item for audit committees

- Publish separate performance data for franchise provision on all OfS metrics

Educational justification requirements:

Each partnership must demonstrate it enhances quality through one or more of:

- Improved geographical access for underserved communities

- Specialist facilities or expertise unavailable on campus

- Targeted support for students with protected characteristics

- Genuine educational innovation (verified through external review)

- Entry pathways for disadvantaged groups with evidence-based wraparound support

3. Financial Transparency and Profit Controls (April 2026)

Cost-recovery principle for universities:

- Limit university fee retention to actual oversight costs only (no profit, no cross-subsidy)

- Require detailed breakdown of: quality assurance costs, administrative functions, mandatory training, clawback provisions

- Mandate quarterly financial reporting with automatic audit triggers for unexplained variances

Work towards profit caps for franchise providers:

- Require full disclosure of all financial flows including: agent commissions, related-party transactions, director remuneration, facilities costs

- Legislate to allow imposition of pre-tax profit margin limit with immediate loss of student loan access for violations

- Create automatic clawback mechanisms where profits exceed any imposed caps retrospectively

Enhanced financial oversight:

- Cross-agency data sharing between OfS, HMRC, Companies House, and Student Loans Company

- Biometric attendance monitoring at providers with suspicious financial patterns

- Real-time monitoring of maintenance loan drawdowns without corresponding fee payments

4. Geographic and Structural Controls (September 2026)

Distance restrictions with specialist exemptions:

- Apply “one hour by car” rule as default requirement between university and franchise provider

- Create fast-track exemption process for innovative partnerships

- Require prior OfS approval for all distant provision with published justification

Volume and programme integrity:

- Cap franchised provision at 25 per cent of university’s total student numbers (reducing to 15 per cent by 2029)

- Prohibit whole-programme subcontracting without prior approval and evidence students access meaningful university facilities/staff

- Extend all controls to validation arrangements to prevent regulatory arbitrage

- Create separate “innovation pathway” for genuinely novel provision verified by external academic review

5. Student Protection and Voice (September 2026)

Independent representation:

- Fund student advocates at all franchise providers through a levy on partnership fees

- Require universities to support students’ unions to extend support and scrutiny to franchised students with separate reporting

- Mandate student satisfaction surveys with >50% response rates, published separately from campus provision

- Establish clear complaints procedures aligned with OfS B conditions with university-level escalation

Enhanced consumer protection:

- Require plain English disclosure of: true continuation rates, employment outcomes, distance from awarding university, profit margins

- Implement mandatory “reflection periods” before enrollment with independent advice access

- Establish hardship funds and compensation funds for students at failed providers funded by sector levy

6. Data, Monitoring and Enforcement (January 2026 onwards)

Real-time oversight:

- Monthly submissions on recruitment patterns, attendance data, assignment submissions, early warning indicators

- Automated alerts for – suspicious recruitment spikes, ghost student patterns, below-threshold attendance

- Cross-reference with HMRC employment data to verify student status

Unified regulatory approach:

- Joint FE/HE audit framework covering both funding compliance and quality standards

- Shared intelligence protocols between education regulators, law enforcement, and border agencies

- Annual review process with rapid policy adjustment capability

Transparency requirements:

- Public dashboard showing all partnership performance data updated quarterly

- Mandatory disclosure of – financial arrangements, geographic locations, agent relationships, related companies

- Annual sector reporting on franchise provision impact and outcomes

7. System Learning and Innovation Support (Ongoing)

Cross-sector knowledge transfer:

- Establish joint FE-HE implementation group with practitioner representation

- Create policy learning protocols preventing regulatory amnesia across government departments

Innovation pathway:

- Channel 4 model enabling small providers to deliver excellence without full institutional infrastructure

- Fast-track approval for verified educational innovation with enhanced monitoring

- Support genuine widening participation through evidence-based partnerships

Implementation flexibility:

- Avoid FE’s “postcode lottery” through consistent national interpretation

- Regular consultation with quality providers to reduce administrative burden

- Built-in review mechanisms with annual policy adjustment capability

8. Anti-Fraud and Enforcement Powers (Immediate)

Criminal justice coordination:

- Dedicated fraud investigation unit with powers to freeze student loan payments

- Systematic prosecution of organised fraud with asset recovery

- Intelligence sharing with the National Crime Agency and border agencies

Enhanced detection capabilities:

- Biometric attendance systems at high-risk providers

- Cross-matching of student loan, tax, and immigration data

- Mandatory reporting of suspicious recruitment patterns

Graduated sanctions:

- Immediate suspension of student loan access for serious breaches

- Financial penalties for universities failing in oversight duties

- Director disqualification for systematic fraud

- Civil recovery of misappropriated funds

Implementation Timeline

Phase 1 (January-March 2026): Emergency measures and fraud investigation

Phase 2 (April-September 2026): Governance, financial, and geographic controls

Phase 3 (September 2026-April 2027): Student protection and full registration requirement

Phase 4 (April 2027 onwards): System learning and continuous improvement

This phased approach enables immediate protection while building robust long-term oversight. Each phase builds upon the previous one, ensuring practical implementation informed by operational experience. The timeline reflects urgency while avoiding FE’s implementation tangles that confused practitioners and delayed effective oversight.

11

The choice

The evidence is overwhelming – franchise abuses in higher education mirror those previously seen in further education. The solutions are proven – ESFA’s reforms successfully addressed identical problems. The only question is whether we will apply these lessons – enhanced by implementation experience – or repeat history.

Critics will argue rapid implementation risks unintended consequences. They will invoke innovation, access, and autonomy. These concerns echo FE’s experience – where quality providers adapted while exploitative ones exited.

But we must learn from FE’s gaps too – avoiding excessive burden on genuine specialists, ensuring consistent oversight, and maintaining flexibility for real innovation.

The government must choose. Continue leisurely consultation while billions flow to dubious providers and thousands accumulate worthless debt. Or demonstrate that policy learning crosses sectors, that student protection trumps vested interests, and that public money demands proper stewardship.

The choice extends beyond education policy. At a time when public services face unprecedented pressure and every pound matters, can we afford to finance 53 per cent profit margins? When trust in institutions continues to erode, can we tolerate preventable scandals? When rebalancing the national economy remains a priority, can we accept provision that exploits rather than empowers disadvantaged communities?

The central question posed by this paper – why is government’s memory so short? – reveals uncomfortable truths about policy-making silos, regulatory capture, and vested interests. Nevertheless, recognising these barriers enables overcoming them.

The franchise crisis represents not novel challenges but familiar problems with proven solutions. FE’s reforms, enhanced by implementation lessons, offer a blueprint requiring only adaptation, not invention. What we lack is not knowledge but will – the will to learn across boundaries, to act on evidence, and to protect the vulnerable over the powerful.

It is arguable whether a sector that prides itself on knowledge creation can claim credibility while proving incapable of institutional learning. A government promising change contemplates timelines extending beyond likely electoral cycles. A regulator established specifically to prevent past scandals watches identical scandals unfold.

Under the new economic paradigm of constrained resources and maximum accountability, repeating expensive mistakes becomes doubly unacceptable. When solutions exist – tested, refined, ready – delay represents not prudence but negligence.

This paper’s recommendations balance proven approaches with implementation wisdom. They protect students whilst enabling genuine innovation – commissioning excellence without requiring full infrastructure. They ensure financial probity through cost recovery and profit caps, while avoiding strangulation. They represent not perfection but pragmatism – the art of the possible informed by the lessons of the actual.

The tools exist, the evidence compels, and the solutions await.

References

Advance HE (n.d.). Governor view: franchise arrangements. [online] York: Advance HE.

Ashworth, S. (2024). It’s time to take on the subcontracting profiteers. FE Week, [online].

Association of Colleges (n.d.). Written evidence submitted. [online] London: UK Parliament.

Centre for Health and the Public Interest (CHPI) (2019). Plugging the leaks in the UK care home industry. [online] London: CHPI.

Centre for Health and the Public Interest (CHPI) (n.d.). How to regulate the profits of public service providers. [online] London: CHPI.

Department for Education (2024). Franchising in higher education. [online] London: Gov.uk.

Dickinson, J. (2023). OfS insight on the risks of franchising fall short at addressing the incentives. Wonkhe, [online].

Dickinson, J. (2024). Some students take maintenance loans but not fee loans and nobody knows what is going on. Wonkhe, [online].

Dickinson, J. (2024). The question on regulating franchising isn’t how, it’s why. Wonkhe, [online].

Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA) (2024). Common findings from assurance work on post-16 education providers: 2023 to 2024 assurance year. [online] London: Gov.uk.

National Audit Office (2024). Investigation into student finance for study at franchised higher education providers. [online] London: NAO.

National Audit Office (2024). Investigation into student finance for study at franchised higher education providers – Full Report. [online] London: NAO.

National Audit Office (2024). Investigation into student finance for study at franchised higher education providers – Summary. [online] London: NAO.

Office for Students (2024). Insight Brief 22: Subcontractual arrangements. [online] Bristol: OfS.

Office for Students (2024). Subcontractual arrangements in higher education. [online] Bristol: OfS.

Office for Students (n.d.). Subcontractual partnership student outcomes dashboard. [online] Bristol: OfS.

The Telegraph (2014). Illiterate builder in £400,000 fake student loan trafficking scam, court hears. The Telegraph, [online] 27 November.

The Times (2023). Walk-in degrees sold in UK. The Times, [online].

UK Parliament (2025). Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill. [online] London: UK Parliament.

- Executive summary

- The franchise explosion: Déjà vu all over again

- The anatomy of exploitation

- Why memory matters: The FE precedent

- Learning from FE’s experience: strengths and gaps

- Why DfE’s current proposals fall short

- The political economy of forgetting

- The cost of delay

- The translation challenge: From FE to HE

- Recommendations: A comprehensive reform package

- The choice